|

|

Bresnahan employs natural materials that he finds around him in each step of the process of making ceramic objects. He is committed to using SUSTAINABLE resources and recycled waste materials from the surrounding area. His philosophy corresponds both with a Japanese sensitivity to nature and with the commitment of Benedictine monks to preserve natural resources. Instead of being discarded, eighteen thousand tons of clay taken out of a road construction project were moved onto the grounds of St. John's University at Collegeville, Minnesota. It will provide resources for Bresnahan and others for the next hundred-plus years. In the same spirit of conservation, the water used for washing the clay is filtered and reused.

|

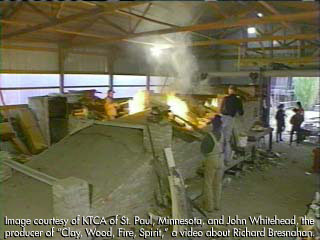

Bresnahan has built a special wood-firing kiln at St. John's out of recycled brick and other materials. It is fueled by deadfall from trees on the monastery's grounds and waste wood from local manufacturers. Modeled after an ancient TUNNEL KILN used in Japan in the twelfth century, the new kiln's design and construction combine information Bresnahan learned in Japan with his own theories about wood-firing. He named the kiln "Johanna" after his teacher, Sister Johanna Becker, a scholar of Japanese art and ceramic specialist at St. John's, who strongly influenced his decision to become a potter.

The kiln has four chambers, each serving a distinctly different purpose. The front chamber, where the fire is built and stoked, is for producing natural glazing. Ash from the wood bark is deposited on the pots, melts in the intense heat, and fuses with the SILICA in the clay to form colorful, shimmering patterns. The second chamber, cooler than the first, contains pieces covered with glazes made from the ashes of local waste materials such as sunflower hulls or navy bean straw.

The teapot was fired in the Tanegashima, or third and largest chamber, which duplicates a relatively new process first created in kilns on Tanegashima Island, off the coast of Japan. The pottery here is unglazed, as in the first chamber. But the results are quite different. Three channels in the floor introduce water into the kiln at high temperatures, which increases OXIDATION. This produces patterns with wide color variations, from soft blacks to vibrant reds, oranges, browns, and blues. The key to achieving the rich, dramatic range of Tanegashima colors lies in the fourth underground kiln chamber, which contains no pots at all. Its seven ATMOSPHERIC DAMPERS force air back into the kiln. This raises the heat and air pressure, enabling the other three chambers to work together. A successful firing is not determined by where the pots are placed in the kiln; rather, the secret lies in "where the pots are not."

Twenty-one people worked in shifts around the clock for nine days to satisfy the needs of this fire-beathing "dragon." The kiln reached internal temperatures of over 2500 degrees Fahrenheit; at this extreme, common clay is among an exclusive group of heat-resistant earthly compounds that can hold together. The teapot was among eight thousand ceramic objects that were fired.

Key ideas.

Where does it come from?

What does it look like?

How was it used?

How was it made?

How big is it?

Who Knows?

Additional resources.