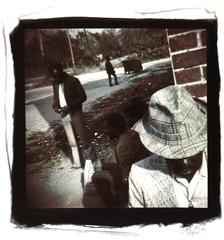

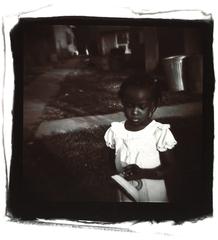

|

The writing

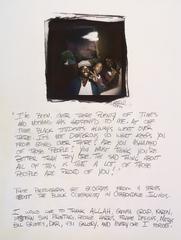

on the photograph:

“I’ve

been over there plenty of times and nothing has happened to me.

At one time black students always went over there. It’s not

dangerous so what keeps you from going over there? Are you ashamed

of those people? You must think you’re better than they are.

The sad thing about all of this is that alot of those people are

proud of you!”

These photographs

are excerpts from a series about the black community in Carbondale,

Illinois.

I would like

to thank ALLAH, Gamma Group, Karen, Western Sun printing, George

Harris, Frame Designs, Matrix, Bill Grimes, Dar, 431 Gallery, and

everyone I forgot.

|

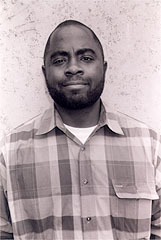

Photographer Carl Pope intended

this picture to introduce his series of photographs documenting the black

community of Carbondale, Illinois. Carbondale is near Southern Illinois

University, where Pope was a student. The photograph and accompanying

text, Pope explains, “indirectly speaks about the history of the

people in the black community in Carbondale. The history of this area

in Carbondale is that they embraced the black students who came there.

They were proud of the black students who came there, even though it was

a poor community. On the weekends the black students would spend a lot

of time in that neighborhood getting their hair cut, partying in the clubs

on Friday and Saturday nights.”“But because of drugs and upward

mobility and possibly integration, the black students quit going over

there and there began to be an animosity and sort of a hierarchy between

the black students and the townspeople. There began to be rhetoric about

that neighborhood ‘across the tracks,’ about the townspeople:

‘you shouldn’t go over there, its dangerous.’ It was probably

true,” says Pope. “Because of the growing split between the

haves and the have-nots and drugs and alcoholism and hopelessness, there

was probably anger and resentment. It wasn’t always that way but

it had started when I got there.”

The writing on the photograph is a quote from a conversation Pope had

about how it is not dangerous in the Carbondale neighborhood, but the

kids in the photo are showing gang signs. Does Pope think that the picture

contradicts the text?

“I never had any problem,” laughs Pope. “It is just like

my friends who go to Egypt. Right now they say on the news that Egypt

can be dangerous for white Americans. If you are black in Egypt they think

you are African. So the question is: dangerous for who?”

|